Letmestayforaday.com

sponsors always were:

www.ODLO.com

www.pac-safe.com

During my travels newspaper columns were published weekly in the Dutch daily newspaper

This project has been supported by these great and warmhearted companies:

Netherlands:

Paping Buitensport,

ODLO,

IPtower.nl,

AVRO Dutch Broadcasting Org.,

Travelcare, TunaFish,

Book A Tour, StadsRadio Rotterdam; UK:

Lazystudent, KissFM, The Sunday Times,

The Guardian; Isle of Man: SteamPacket/SeaCat; Ireland:

BikeTheBurren;

Belgium: Le Temps Perdu, Majer & Partners; Austria: OhmTV.com;

Norway:

Scanrail Pass, Hurtigruten, Best Western Hotels; South Africa:

eTravel, British

Airways Comair, CapeTalk,

BazBus;

Spain:

Inter Rail, Train

company Renfe; Australia: Channel

9 Television, Bridgeclimb, Harbourjet, SeaFM Central Coast,

Moonshadow Cruises, Australian Zoo, Fraser Island Excursions,

Hamilton Island Resort, FantaSea Cruises, Greyhound/McCafferty's Express Coaches,

Aussie Overlanders, TravelAbout.com.au, Travelworld,

Unlimited Internet,

Kangaroo Island SeaLink,

Acacia Apartments; Malaysia: Aircoast; Canada: VIA rail,

Cedar Springs Lodge,

BCTV/GlobalTV,

St. George Hotel,

VICKI GABEREAU talkshow,

Ziptrek Ecotours,

Whitler Blackcomb Ski Resort,

Summit Ski & Snowboard Rental,

High Mountain BrewHouse,

Cougar Mountain Snowmobiling,

Whistler Question Newspaper,

Snowshoe Inn,

First Air,

Nunanet.com,

Canadian North

Accommodations by the Sea,

DRL Coachlines Newfoundland,

The National Post and

Air North.

Reports

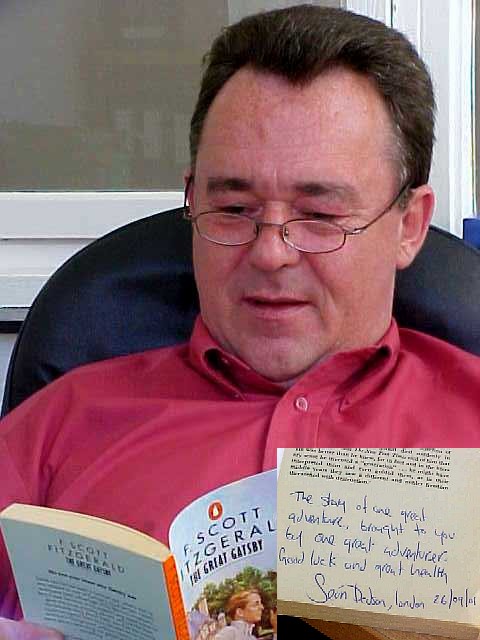

During my travels, I received free accommodation for a night in exchange for writing a daily travel diary. This diary documented how I reached my next destination, the hosts who welcomed me, the food I was offered, and other experiences along the way. Below, you will find the archives of these extensive reports. Please note that English is not my native language, and most entries were written quickly, often around midnight. Enjoy!Tuesday, 9 October 2001

Tamboerskloof --> Rondebosch E., Cape Town (SA)

Today was going to be the big day. Firstly I was waken by Ludo, who told me that the local radio station Cape Talk wanted to have an interview with me, but most important: I am going to visit the Robben Island. A task I never saw as something possible, not even within the first 6 months of this project.

Ludo transported me to the radio station where talk show host Martin Bailie (discovered an old pic of him too, hehe) was very amazed by my way of travelling the world. He kept mentioning the website address as I hoped for more invitations in South Africa and maybe people had family living outside of Cape Town who might like to put me up for the night.

I must say that the invitations in South Africa are coming in balanced. More than two handfuls in the bigger cities as Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban – but the areas in between are also becoming worth a visit.

I am invited in almost every suburb of Cape Town and as I wrote before: the number of suburbs here are countless for a foreigner. The city just stretches out for miles and miles.

The weather in Cape Town has been good since I have been here. What I experience feels like a rare hot summer in The Netherlands, although they call it spring in South Africa. There is just much more to come…

After the radio show I walked back along Long Street towards Ludo’s apartment, settled for a sandwich and around 10.30 it got time to fetch the ferry towards Robben Island.

Yazeed, a reporter of the Cape Times newspaper escorted me on the ferry, introducing me a bit more utterly than the on board video did. He also writes for the newsletter of the island, which is sent to anybody related to the island (ex-prisoners, politicians, etcetera), and wanted to write about me.

It was interesting how he told me that he had been following me for a long time, even before I got to South Africa. “I think I already know you,” he said, although he had never seen me in real life. Yazeed stayed on the boat as I set foot on the island.

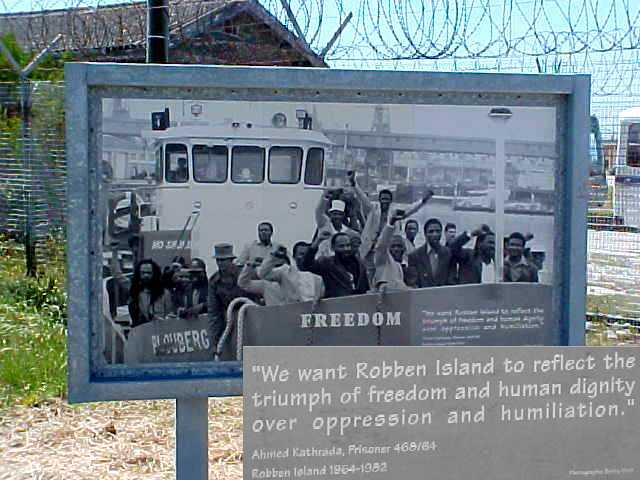

Robben island is situated a simple 11 kilometres from Cape Town, in the middle of Table Bay, within clear sight of the city. The name Robben comes from the Dutch word for seal, and though means Seal Island.

On the island a bus tour took the load of tourists I was in between, along the complete island to end up at the legendary prison.

People lived on Robben Island many thousands of years ago, when the sea channel between the Island and the Cape mainland was not covered with water yet. Since the Dutch settled at the Cape in the mid-1600s, Robben Island has been used primarily as a prison.

Indigenous African leaders, Muslim leaders from the East Indies, Dutch and British settler soldiers and civilians, women, and anti-apartheid activists, including South Africa's first democratic President, Nelson Rohihlahla Mandela and the founding leader of the Pan Africanist Congress, Robert Sobukwe, were all imprisoned on the Island.

Robben Island has not only been used as a prison. It was a training and defence station in World War II (1939-1945) and a “hospital” for leprosy patients, and the mentally and chronically ill (1846-1931). In the 1840s, Robben Island was chosen for a hospital because it was both secure (isolating dangerous cases as leper) and healthy (providing a good environment for cure).

In real life, victims of leprosy where banned from the mainland, separated from their families, to live on the island.

There still is the Gate of Tears, where family members could say a last goodbye to their relatives, after that they would never see them again. Next to the graveyards that is one of the leftovers of that time.

During this time, political and common-law prisoners were still kept on the Island. As there was no cure and little effective treatment available for leprosy, mental illness and other chronic illnesses in the 1800s, Robben Island was a kind of prison for the hospital patients too.

Since 1997 the island has been a museum.

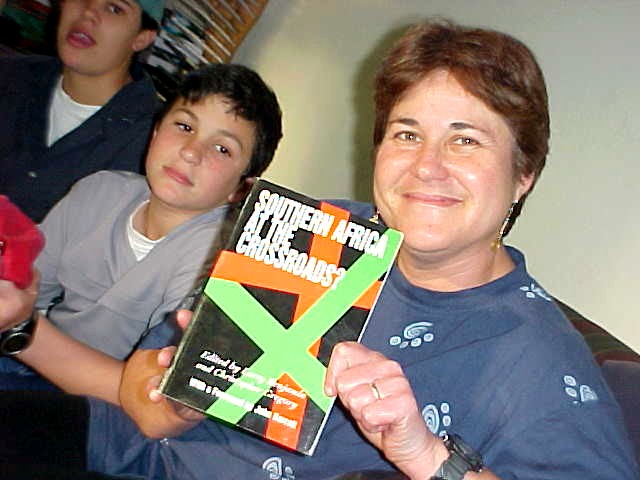

To understand why the Robben Island became an apartheid prison and what the prisoners struggled against during the last 30 years, it is important to know something about Apartheid.

It began in 1948 when the National Party first came to power. There was racial discrimination and seperation before that time but from that year onwards the government passed laws to enforce apartheid. It became the system that ruled every aspect of life in Southern Africa.

Black and white people were kept apart, it kept white people in power and black people without the right to choose the government. Under the Apartheid system, the people of South Africa were segregated according to skin colour. The Nationalist government distinguished between four different groups- Africans, coloureds, Indians and whites- and treated these groups differently. This is why the system was a racist, discrimating one; it was unfair because it applied different laws for each race group.

Black people were separated in many ways from society, not being allowed to vote, study, or being allowed the freedom to express them in thought or speech. Most of all in the ways, which their ancestors taught.

Different laws applied to each group and were unequal and unjust in its specifications. White Anglo Saxon leaders made the rules, owned about 90% of the land and were the only citizens-allowed to vote.

The Group Areas Act forced people to live in seperate areas according to race. The pass laws prevented so-called non-whites from moving around freely, going out at night or working were they chose. It was against the law for blacks and whites to marry or have sex with each other.

Black people could not own houses or property except in very limited areas and were often treated badly and insulting. The government spent six times more on a white child’s education than on a black child’s who didn’t even have to attend school.

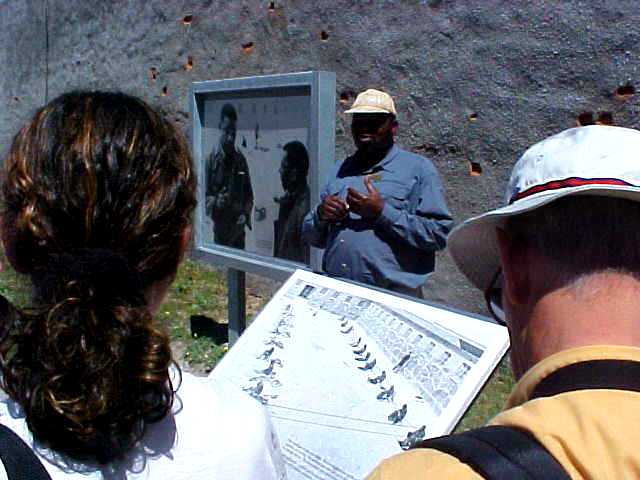

A former prisoner of the Robben Island prison told his story and led the group around the different sites. It was very emotional. I was very impressed by his anecdotes of the horrifying things that happened here and nobody knew about.

Some tourists in my group should have been imprisoned themselves, for interrupting the narrator to ask when they got to see the penguins on the island. How embarrassing unrespectful that was! And they didn’t even seem to feel it like that.

This place is similar to that of the Nazi concentration camps and hideouts: a cold, damp, barren and lonely place. Fresh water and trees were completely absent, and very little communication could be achieved between the outside world and islanders.

Rapers and killers were seen as common-law criminals and therefore sentenced to the medium security prison on the island. Political prisoners were placed under heavy security as they were seen as the most dangerous species of human life.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (1918) was accused with many others of sabotage and conspiracy against the state. In 1964 all of them were sentenced to life imprisonment on the Robben Island. They were fortunate in escaping with their lives, as the maximum penalty for the offences was the death sentence.

Their principled defence and the clumsiness of the prosecutor, Percy Yutar, encouraged the judge to be somewhat merciful, Mandela once said. He also commented in his autobiography: “journeying to Robben Island was like going to another country”.

As prisoner number 488/64, Mandela was to remain on the Island until March 1982. His attitude towards prison was that it was a microcosm of the struggle as a whole. “We would fight inside as we had fought outside... just on different terms.”

The political prisoners were confronted with a loss of personal control, disorientation and isolation, arbitrary punishments, discriminatory regulations and often-cruel prison authorities.

The light in each cell burned all day and all night. Coloured, Indian and African prisoners received different diets, and prisoners were further classified into A, B, C, or D categories, which carried a decreasing number of privileges.

Visits by family and friends were severely restricted, as were the numbers of letters sent and received.

For Mandela the only pleasing prospect of prison was that it gave him time to think and reflect. Yet the prisoners could talk to each other, while cleaning out their sanitary buckets and while working in the quarries and the courtyard. Their struggles for better conditions and privileges, such as permission to study, did achieve some success, with the help of outside pressure.

Although there were general and political tensions, the Robben Islanders were able to form personal and political ties both among themselves and between their different political organisations. It were Nelson Mandela’s powerful words that said: “We have to make this prison into a university!”

Lots of political prisoners later because influential politicians, like the minister of labour in Namibia or even President of the Republic of South Africa, like Nelson Mandela.

The tour through the prison blocks ended and the speaker asked everybody to pass the story on…

My eyes were watery and my nose was runny when I shook the man’s hand at the gate. I wanted to say much more, but my throat was blocked. All I could say was “Thank you”.

“With pleasures," he said.

Everybody was quiet when they walked off the prison vicinity towards the boat, except those few who finally got to see their penguins…

The island bears witness to the triumph of democracy and freedom over oppression and racialism. I experienced the visit to the island with immense power and it really struck me personally.

If I could cry I would have done it, but everything in my body was blocking. Tears ran down while writing this report.

I was back at Ludo’s apartment where I had a nippy nap until my next host, Jon Weinberg, came to pick me up.

I thanked Ludo and Juanita for letting me stay for two nights. We had our ups and downs, but hopefully learned from it.

Jon Weinberg is a museum designer and currently works on the Science Center at the Century City mall.

His brother Paul Weinberg, a well-known photographer in South Africa, accompanied him. He originates from Durban and was in town for a assignment.

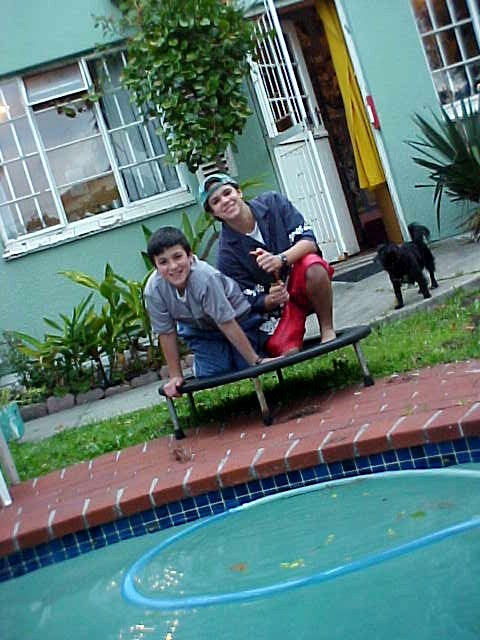

They drove me to their home in Rondebosch East, a less high-class environment than I previously stayed in. Jon is married with Dr. Di Cooper and they have two children, Tara and Michael.

They live in a unpretentious but civilized bungalow where they offered me to stay and sleep in their guest room.

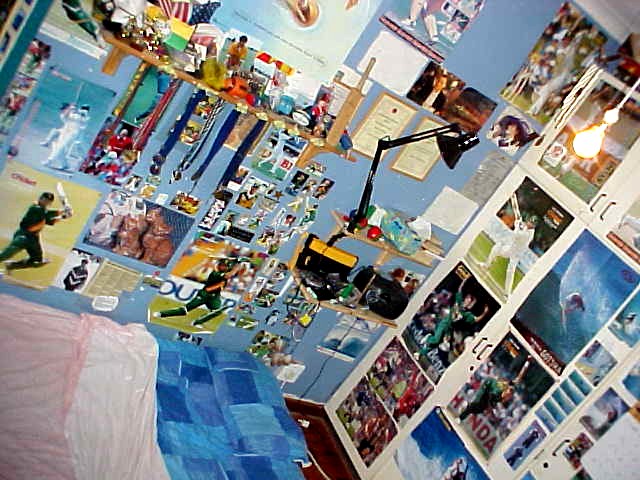

Tara and Michael are both cricket players and wannabe sport stars. Tara’s room is really covered with anything that deals with cricket or rugby.

It were the children who saw a report about my travelling on E-tv and asked their parents if they could invite me over.

Around 7pm the parents started preparing dinner. Di turned on some South African music and suddenly the spicy aromas and the sounds of PJ Powers and Hotline, Mango Groove, Jaluka and the Lady Smith Black Mambazo (placed on the world map by Paul Simon) gave me the experience of the South African family vibe.

Di told me about the 80’s Bright Blue, which lead singer now lives in New York and recently survived the attacks on the World Trade Centre as he was in there.

Their song Weeping is about young white men that refused to do their tour of duty in the South African army, because they had to shoot at the suppressed blacks on the streets.

During dinner in the living room I heard the sounds of a mosque calling for the prayers. I had never experienced such a call before and wasn’t that disturbing at all. It even accumulated with the atmosphere I was already in.

After dinner Jon and Di took us all out for a ride. Basically they were just looking for a place to by smoothies, soft ice cream, but they couldn’t find their exact locations or the shops were already closed at this time of the night. We finally ended walking on the Sea Point Boulevard, where we licked on our bubblegum blue soft ice creams after all.

Back at the house I did some writing on their computer when the whole family got to bed. I got some writing done and headed for the guestroom where I fell asleep.

Today was another day that goes into my memories again as a day with unforgettable experiences.

Good night Rondebosch East!

Ramon.

Where am I at this moment?

Click here to see the map.